Information

Tanya E. Clement

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 University of Texas at Austin

Daniel Carter

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 University of Texas at Austin

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Please visit the final version of Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities, where you can read the revised keywords and create your own collections of artifacts.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 The official reviewing period for this project has ended, and commenting is closed.

CURATORIAL STATEMENT

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 In the data, information, knowledge, wisdom (DIKW) hierarchy that circulates through Knowledge Management (KM) and Information Science (IS) discussions, data appears at the base of a pyramid of which wisdom is the pinnacle. In this schematic, data is “raw” and lacking in meaning, while information, the next higher level of the pyramid—just below knowledge and then wisdom—represents the presence of added links and relationships; information is higher up on the wisdom chain because it is data made meaningful (Sharma 2004). At the same time, in digital humanities pedagogy, discussions that teach students about data have typically reflected a more critical understanding of data as capta (Drucker 2011). That is, we teach students that data is not found in the “raw” but has rather been cooked all along, taken and constructed, seasoned according to our situated contexts—a dash of access issues (Where is the data?); a pinch of media, format, and technology constraints (How is the data?); a squeeze of the juice that is cultural bias (What is the data? Who is involved in and impacted by its creation and use?). In these contexts, we teach students that data is served already seasoned and that they have to learn to discern not only its different flavors but to better understand the cooks in the kitchen. So, what is the nature of information pedagogy?

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Learning to think critically about information means rejecting illusions of objectivity, impersonality, atemporality, and authorlessness aspects of information more generally; it means we learn to talk about the personal, subjective and situated contexts of our readings in the context of information systems. Accordingly, with such a critical perspective, we learn to write—or conceive of or even develop—information systems in ways that bely these concerns. To teach students to think about information from this more critical perspective means first understanding how we as a culture tend to think of information. In literary culture, for example, information has taken on the flavor of what KM and IS view as raw data. Pitted against “the literary,” information has been considered an authorless and uninterpretable gush that distracts our attention from more important topics of concern (Marche 2012). This is not just a 21st-century perspective, fostered in the digital age; it is a critique we also see in T.S. Eliot’s “The Rock”: “Where is the Life we have lost in living? Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” (1934) We see it as well in Gertrude Stein’s short piece “Reflection on the Atomic Bomb”: “They asked me what I thought of the atomic bomb. I said I had not been able to take any interest in it . . . Everybody gets so much information all day long that they lose their common sense. They listen so much that they forget to be natural. This is a nice story” (1946). More recently, in a discussion on Kenneth Goldsmith’s “uncreative” poetry in PMLA, Scott Pound writes that Goldsmith’s method for transcribing speech from recordings of every-day conversations and radio shows (not to mention his conceptual art project “Printing out the Internet” and his controversial decision to perform Michael Brown’s autopsy as poetry) is “poetry that treats language as so much data or information, chosen for its quantitative rather than its qualitative allure, prized for its mass and availability rather than its originality or aesthetic value” (317-3-18). The information students see in these contexts is represented as so much junk: while considered factual and evidentiary, it is abstract, autonomous, and objective—a massive, available, st(r)eaming raw data dump over which they have very little agency. On the contrary, we can teach our students that digital, networked information systems reflect cultural contexts and can serve as a means for voicing those perspectives.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 The pedagogical resources gathered here provide an opportunity to understand information pedagogy as learning agential modes of reading and writing in the context of information systems. To this end, we have used Michael Buckland’s three meanings for information to guide our selection criteria: information-as-knowledge, information-as-thing, and information-as-process. For Buckland, an understanding of information-as-knowledge underpins a critical stance towards information generally since knowledge is personal, subjective, and conceptual; information-as-thing requires a critical stance to its material nature since to communicate the personal, the subjective, and the conceptual “they have to be expressed, described, or represented in some physical way, as a signal, text, or communication” (351); information-as-process or “the act of informing” necessitates a consideration for what Foucault would call “an archaeology of knowledge—or a consideration for the systems of power and influence that shape the information systems that process information-as-thing and therefore knowledge production, identity construction, and intersubjectivity. As such, these lessons show how arguments, thoughts, and creative expressions are asserted through information systems, because these lessons foreground a perspective in which the informativeness or information-ness of content (its relevance to information seeking) is shaped by our understanding of the content’s social context, its form, and our own ideas about how we go about understanding the world.

CURATED ARTIFACTS

DH101: Intro to DH

screenshot

- ¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

- Source: http://dh101.humanities.ucla.edu/

- Creator: Johanna Drucker (University of California, Los Angeles)

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 This syllabus for an undergraduate course is a useful pedagogical tool because it asks students to consider the relationship between data and information as one that is shaped by the organization of data into a structure. For example, the module “Data and Databases” is particularly strong since students are introduced to the idea that data are capta or phenomena that are considered, by nature, quantifiable and thus, adherent to a prescribed scale or unit or system of measurement. Seen this way, students can understand that structured data can preclude certain modes of interpretation (subjective, non-normative) while facilitating others. Further, the tutorial “Managing Data” using Google Drive’s Fusion Tables guides students through the process of considering a series of questions about overarching concepts such as data creation, data management, and data visualization through the process of visualizing a network from a data table they have constructed. While this lesson is achieved using the complex network maintained by the characters of a somewhat outdated television drama (Lost), the point of the lesson, that students are organizing information they think they already know in order to structure it and categorize it into types of their own choosing, forces students to reduce complex knowledge into data points and relationships that others would find informative or relevant. Learning to upload their data and create an undirected graph using Google’s Fusion Tables lends a real-world lens to the lesson as would the use of any tool that has wide, general use. Because students are asked to compare their network graph to the information rich spreadsheet they originally created, they are reminded to consider how entities may easily defy labels and how the various relationships could be represented differently. The ultimate benefit of this course is that students learn to think critically about how ambiguities that are present in subjective content may be hidden in structured data formats and how they have the agency to change those structures to tell a different story.

Design Transformation

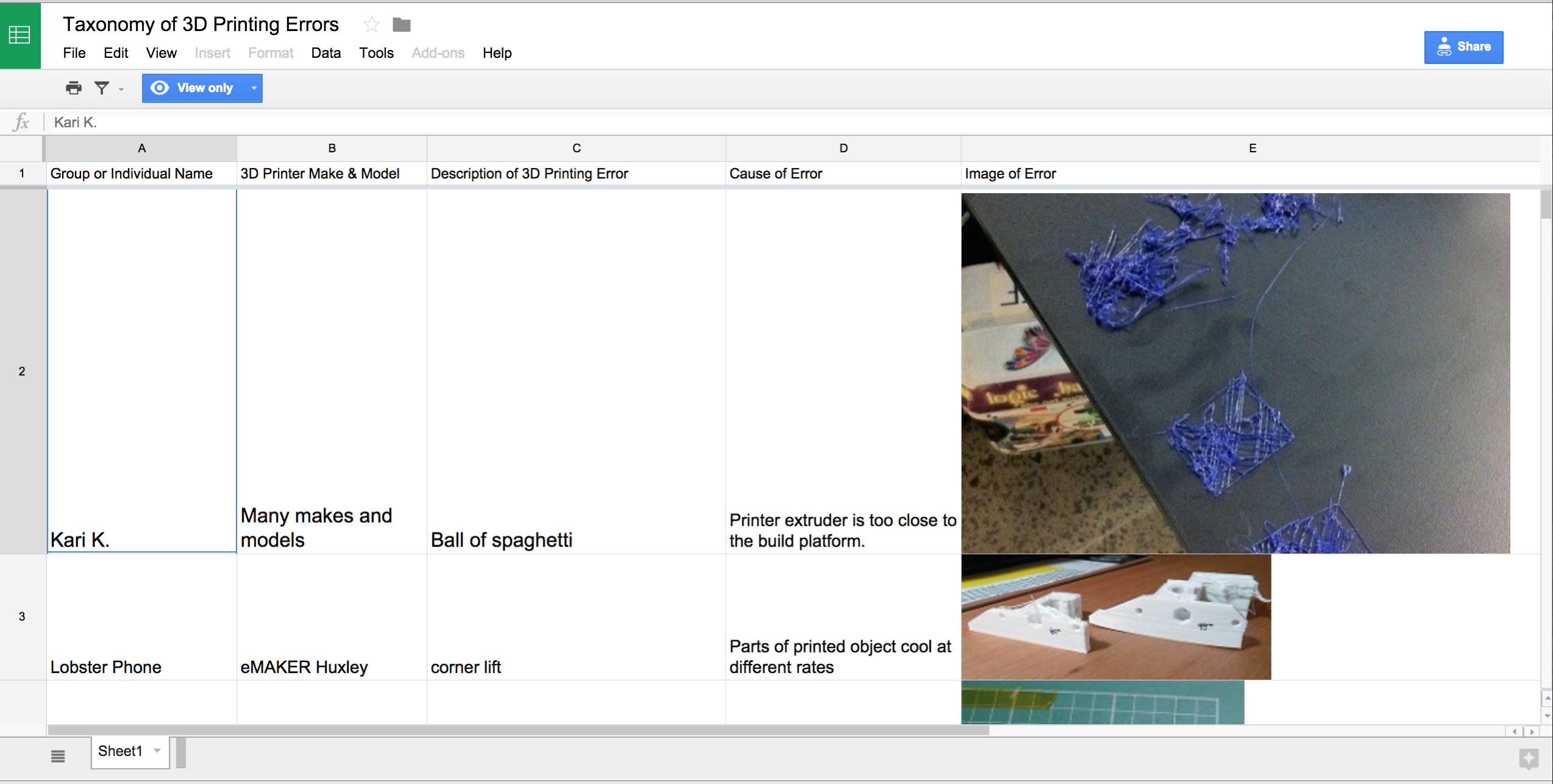

screenshot

- ¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

- Source: http://courses.ischool.utexas.edu/feinberg/2014/spring/INF385U/assignments.html

- Creator: Melanie Feinberg (University of North Carolina)

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 The central strength of the course in which this assignment appears is its consideration for the active role that students can learn to take in developing information systems. The assignment, “Design Transformation”, is particularly useful for its investigation into the transformative possibilities enacted by expressing and representing residuality, or the experience of being insufficiently described via a classification system. The assignment is powerful because it shows students how they can actively enact residuality as part of an information collection’s metadata or descriptive infrastructure. With this objective in mind, this assignment asks students to revise the descriptive infrastructure (including the metadata and other customizable elements) of an existing digital collection to create an experimental transformation according to their own arguments or perspectives. Students are asked to identify an overall design approach and to consider how descriptors, summaries/abstracts, titles, responsible entities, dates, key frames, tags, collections and playlists can be potential design elements that can be used to realize residuality. As a project-based assignment, students actually implement their revised design using the Open Video Digital Library Toolkit, or OVDLT, an digital video library development system that was created by Gary Geisler, as well as produce a written piece in which they think critically about the modes of reading and writing that are available for argumentation and expression in information systems. As a result, students are led to articulate their interpretive understanding of constituent materials, of what collection authorship entails, and to consider how digital collection design environments are also authoring environments.

Data-Based Project and Analysis

screenshot

- ¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

- Source: http://lkleincourses.lmc.gatech.edu/data13/files/2013/01/final.pdf

- Creators: Lauren Klein (Georgia Tech)

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Like Feinberg’s course, described above, this course usefully engages with information as authored by explicitly asking students to first understand and then to intervene in existing systems or processes in order to create an argument. However, while Feinberg’s course focuses on a specific aspect of information systems (metadata) and a specific theoretical concept (residuality), Klein’s course asks students to discover and articulate their own interests, which might range from forms of visualization to formats of data and from epistemological issues to the social or political. Likewise, the final product of the project is left open to students, with guidelines that it may be as simple as an image or as complex as a complete system, in which case a proof-of-concept or proposal might be submitted. This breadth is valuable not just for giving students the opportunity to pursue their own interests and to further develop projects initiated earlier in the course but also for asking them to think about the technical consequences of their choices. Whether producing a proof-of-concept or a proposal, students must think about how their critical arguments intersect with real world constraints. Indeed, real world examples of data visualization provide students something to both push against and work toward. Projects such as Nicholas Felton’s personal annual reports are especially valuable objects to think alongside, as they represent uses of data that are personal and emerging, open to a variety of arguments and interventions, as well as concrete and specific, realized in specific technologies that are available to students. One of the interesting tensions running through the assignments collected here is between information as crafted by individuals and information as structured by distributed technical systems and tools, and one of the key pedagogical uses of Klein’s project is in having students experience and negotiate this tension.

Printing Fictions

screenshot

- ¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

- Source: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ELJW5jNMvA7kkXKKX8aMXPzIcPCkCROAQ3O6IyVC0pw/edit

- Creator: Kari Kraus (University of Maryland, College Park)

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Information is not just about contextualizing data. The machines we use to generate, manage, understand, and share our views of the world are also part of how we think critically about the information landscape. This assignment for graduate and undergraduate students is of note because it asks students to consider how information infrastructure errors may be inspirational and spur innovative design. Using Philip K. Dick’s “Pay for the Printer” story of 3-D printed things as a motivational premise for considering the advantages of machine error, the assignment “Printing Fictions” gives students the opportunity to design their own versions of the deformed artifacts, tools, and objects described in Dick’s post-apocalyptic world. First adding to a “taxonomy of errors” to systematically document and classify 3-D printing errors, students use this canvas of problems as a spur for potentiality as they eventually form the basis of a diorama they build with their error-inspired 3-D artifacts. This process of collection and categorization includes documenting one or more 3-D printers (make and model) associated with the error; a description of the error; the cause of it; an image of it; and the source for more details about it. In addition to contributing entries to the spreadsheet, all of the students are asked to organize, group, or classify the errors into a meaningful system. Through this assignment, students are introduced to a critical perspective on the value of noticing and interrogating a technology’s “break down” or the moments in which the processes or algorithms of an information system such as a 3-D printer become apparent to the user; more important, they are empowered to use these moments to enact previously unimagined uses for which the machine was not originally intended.

Information and Contemplation

screenshot

- ¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

- Source: http://cyborganthropology.com/Infomation_and_Contemplation:_University_of_Washington_Information_School

- Creator: David Levy (University of Washington)

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 This assignment is part of a course on information and contemplation designed to investigate contemporary questions of information overload and the fragmentation of attention. Unlike other artifacts collected here, which tend to draw attention to data or the technical systems through which they move, this assignment is valuable for its focus on the individual experience of systems such as email and social media platforms. Students are asked to consider not just what these systems are and how they function but also how they structure the rhythms of life and makes themselves felt on a bodily level. Students examine their information practices by keeping a journal of their email use and later reflecting on patterns found there, as well as alternative practices that might respond to these patterns. By highlighting the lived experience of contemporary technologies, the assignment provides students with a toolkit for critically reflecting on the practices that form the invisible background of everyday life. However, as the assignment brings students to understand, while they may be invisible, these practices tie into a wide range of systems including the social, biological, phenomenological, and technical. While the process of reflection that Levy advocates is a simple one, it usefully points out the value of observing the life of data (and of humans) in the wild. Together with Loukissas’s project, discussed below, this project begins to introduce students to field methods that can enliven data and information systems, opening them to new modes of interpretation.

The Life and Death of Data

screenshot

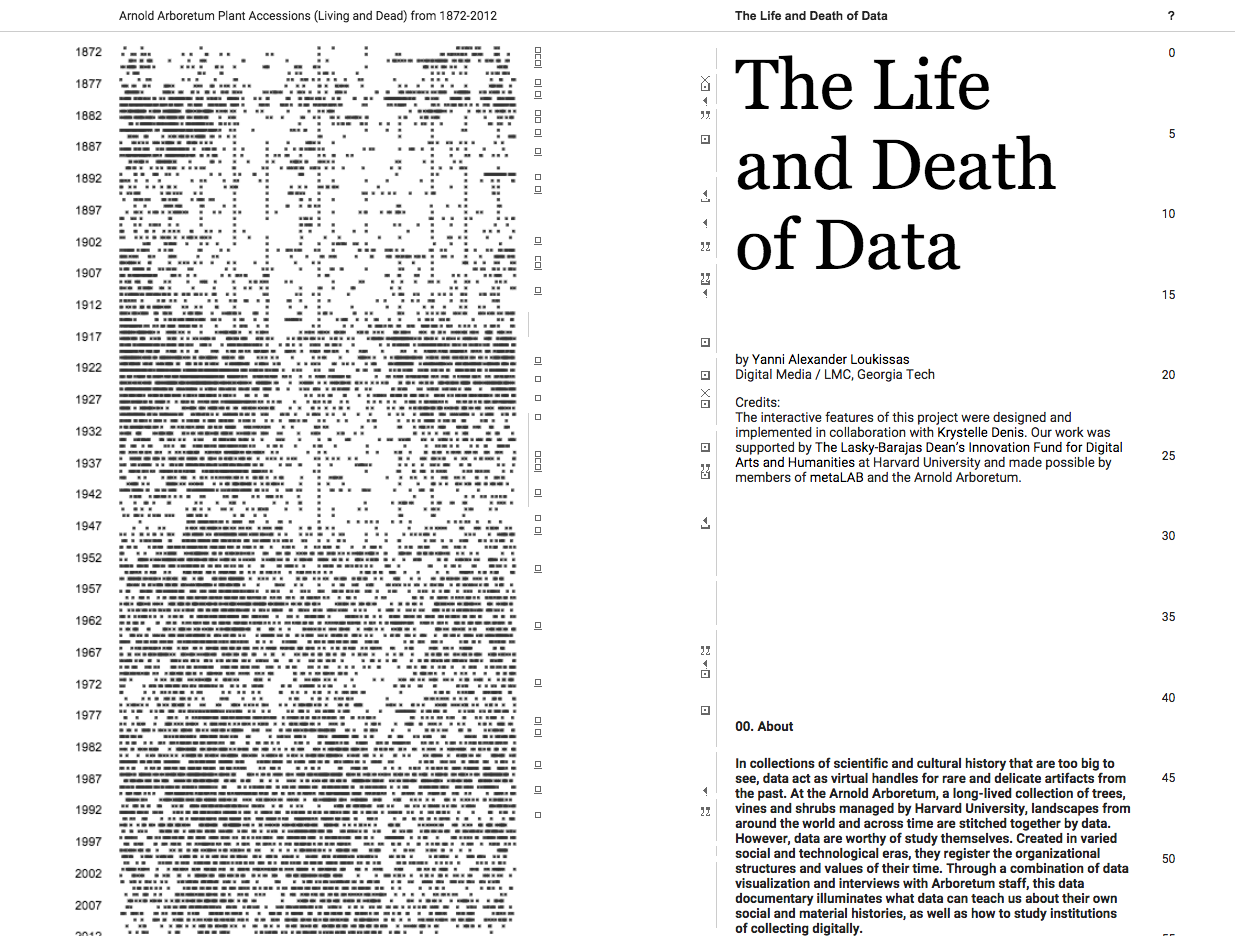

- ¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

- Source: http://lifeanddeathofdata.org/

- Creator: Yanni Loukissas (Georgia Tech)

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 This project, titled “The Life and Death of Data” and described by its creator as a “data documentary,” is included here as an example of how data, seen through processes of collection and transformation, can be not only an object of inquiry but also a means of communicating or informing. The project focuses on the accession records of the Arnold Arboretum, a collection of trees and other plants managed by Harvard University. Accompanied by a visualization of these data, the text draws on interviews with arboretum staff to construct an institutional narrative that centers on the organizational structures and values that influence collection and documentation practices. Within this narrative, somewhere between digital records and personal interviews, the workings of information-as-process become visible. One of the strengths of the project, as a pedagogical artifact, is this movement between different realms that are often left separate—the project reveals to students, through a concrete example, that to fully understand data, you have to talk to people; that records have histories as rich as (and inseparable from) institutions; and that data visualizations do not so much present facts as make rhetorical arguments. Like the information collected and organized by the Arnold Arboreteum, Loukissas’s essay emerges in a specific historical context (e.g., the rise to popularity of JavaScript frameworks for visualizing data in the web browser) and should be read with this in mind. The form of the project, with an extensive essay running alongside an interactive data visualization, reveals itself as intentionally crafted and serves as a useful example of the kind of work that other assignments gathered here ask students to produce. Assignments such as those by Feinberg and Klein ask students to make an argument in the form of a data visualization or information system and then to make an argument about their artifact in the form of a conventional essay. Loukissas’s project is valuable for modeling how these two tasks might come together in a single artifact that combines both visualization and text.

Performing the Algorithm

screenshot

- ¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

- Source: https://www.hastac.org/blogs/jarah/2011/10/10/code-concepts-i-performing-algorithm

- Creator: Jarah Moesch (University of Maryland, College Park)

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 “Performing the Algorithm” is an activity developed for the Digital Cultures and Creativity program at the University of Maryland, College Park. The strength of the activity is in giving students a basic conceptual understanding of algorithms, from which the kinds of critiques asked for by other assignments collected here might build. In the activity, groups of students create algorithms, or sets of instructions, for moving through and engaging space (defined broadly, with physical, virtual and conceptual spaces all given as examples). Examples of algorithms created in this way include instructions to play a game, perform a play, or enact a programming principle. Rather than asking students to directly critique existing information processes, this activity focuses on giving them the conceptual understanding, gained through practice, on which future critiques might build. This understanding is especially important for giving students with less technical backgrounds the opportunity to make arguments that, nevertheless, draw on an accurate (if rudimentary) understanding of information processes. This concrete approach to working toward understanding is especially important for topics like algorithms, which are common in public discourse but can often take the form of vague metaphors or magical black boxes. In the tradition of critical making, Moesch’s activity works to move past these popular understandings by giving students a way to experience some of the technical realities that may otherwise be masked. Modifications to the activity, perhaps for students with more technical skills, might include having students create and act out algorithms for information processes such as those dealt with by Shaw’s assignment, below.

Data Critique

screenshot

- ¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0

- Source: http://courses.digitaldavidson.net/dig210/guidelines/data-critique/

- Creator: Mark Sample (Davidson College)

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 This assignment is part of a larger undergraduate course in the Digital Studies interdisciplinary minor at Davidson College. It seeks to teach students to think critically about how an understanding of data and databases ties to the ways in which we understand the world. That the assignment, “Data Critique,” had been previously developed by Lauren Klein in her class, “Studies in Communication and Culture: Data” [http://lkleincourses.lmc.gatech.edu/data13/files/2013/01/midterm1.pdf], and later redesigned in Tanya Clement’s graduate-level “Introduction to Digital Humanities” class https://www.ischool.utexas.edu/sites/default/files/images/webform/DHFall2015Syllabus.pdf shows its utility as a a means for encouraging students to think more critically about the origins of datasets they are using, but Sample’s version is selected here for its inclusion of particular questions for deeper consideration. The questions, influenced by a blog post by Michael Sacasas entitled, “Do Artifacts Have Ethics?”, show a keen understanding for the kinds of agency that information systems can afford. Specifically, in asking students to think about datasets as “articulations of power, with built-in assumptions, silences, and even anxieties,” Sample’s assignment, like Klein’s, asks students to find a dataset (or to consider a dataset they may have created themselves) and interrogate its origins and what kinds of interrogations it foregrounds. But Sample’s questions also encourage students to imagine what Sacasas calls the “moral dimension” of informativeness. This moral dimension means considering alternative affordances, not only what the dataset foregrounds but also who and what it occludes and what impact those occlusions and omissions may have on who can interact with it and to what ends. The end result is a paper that not only discusses the social and cultural context of the dataset but also considers how we empower dataset designers to incorporate ommitted voices and perspectives. The strength behind this assignment is the extent to which it requires students to consider how we can empower people to consider the nature of what is informative in terms of its implicit claims about the world.

Designing a State Machine

screenshot

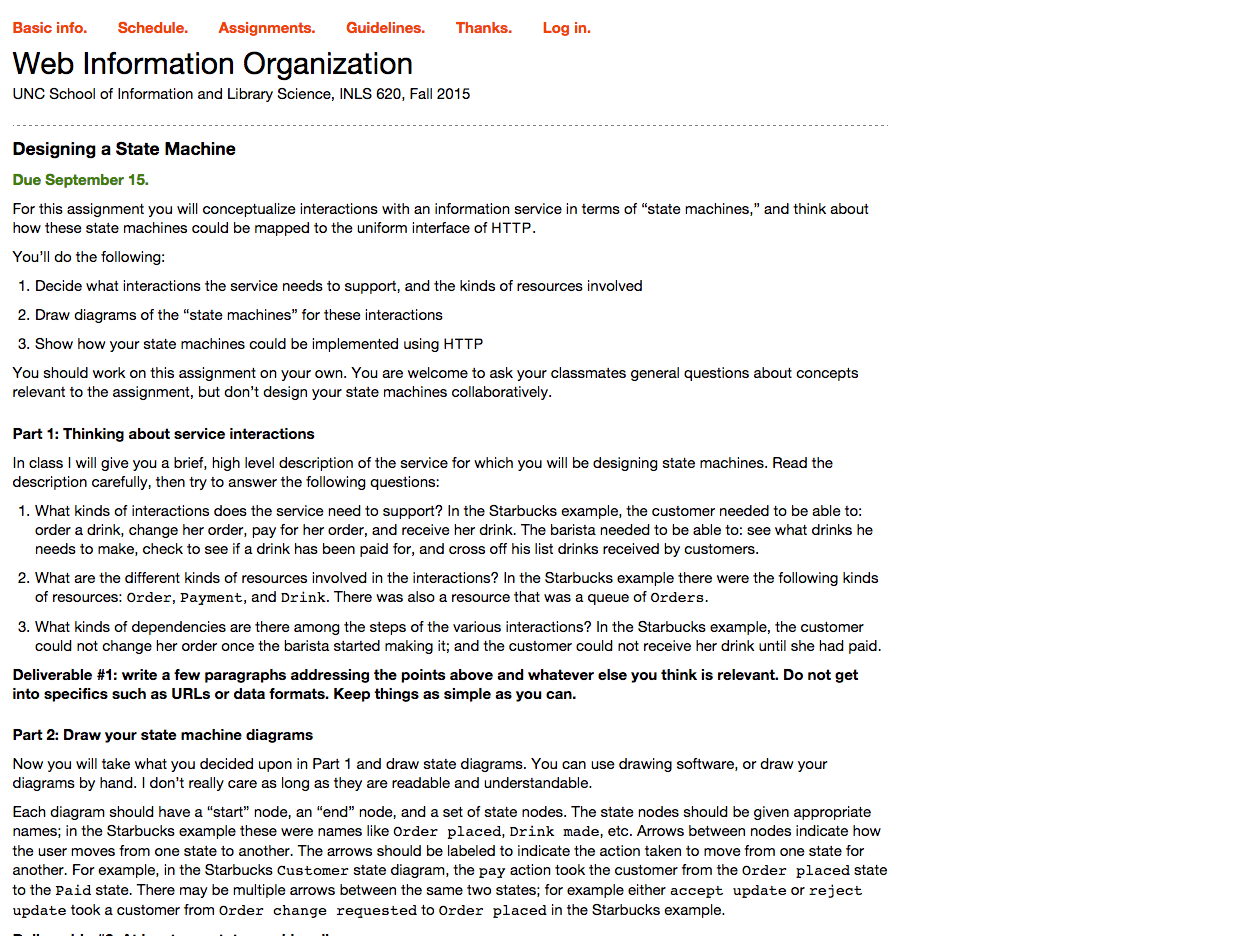

- ¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0

- Source: https://aeshin.org/teaching/inls-620/2015/fa/assignments/

- Creator: Ryan Shaw (University of North Carolina)

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 Ryan Shaw’s “Designing a State Machine” assignment, part of a graduate-level course on Web Information Organization, asks students to consider how real-world interactions such as ordering a cup of coffee at Starbucks could be modeled as information systems and implemented using contemporary web technologies such as HTTP. The assignment consists of several steps: students first describe a context and identify the relevant interactions (e.g., ordering a drink), resources (e.g., an order, a drink, a payment) and dependencies (e.g., a customer cannot pay for a drink before it is ordered). Students then diagram the “states” involved and how they are traversed—for example, moving from the “order placed” state to the “payment received” state is accomplished through the action of paying. The final step of the project calls for students to describe how the system could be implemented using contemporary internet protocols. Like others collected here, the assignment is valuable for providing students with a way to engage with technical specificities while simultaneously thinking about the way those specificities structure interactions in the world. Unlike other assignments, however, the level of focus of Shaw’s assignment allows students to think about the different protocols or logics that underlie information processes that may otherwise appear distinct. Protocols such as HTTP and standards such as Unicode have consequences similar to those of the organization schemes and data models that other assignments here highlight; however, they are arguably more invisible and easier to elide in analysis. While not explicitly critical, Shaw’s assignment is valuable, then, for making explicit the invisible protocols that structure common information processes and for providing students with a way to think about these protocols in relation to their everyday lives. The infrastructural undercurrents of this assignment could be pursued through a reading such as Edwards (2003), which considers the development of the internet in relation to both micro (e.g., individuals and small groups) and macro (e.g., political economies and governments) contexts.

Descriptive Schema

screenshot

- ¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

- Source: https://utexas.instructure.com/courses/1160641/assignments/3735626

- Creators: Karen Wickett (University of Texas at Austin)

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 This assignment is part of a larger graduate course on organizing information at the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin. In the assignment, students are asked to define a set of entities, articulate a motivating purpose for describing them, and then outline a structure of attributes and associated values to systematically represent their entities as metadata. When defining the class of entities, students are required to think critically about the range of possible instances that would fit into their sets and possible “border” cases: “For example, is a photo in the airport an acceptable instance of Scotland vacation photo? Is an establishment that serves burritos but no tacos an acceptable instance of taqueria?” The central impact of this assignment is its requirement for the consideration of border cases. This central concern encourages students to acknowledge their agency in creating attributes that apply equally to a more various membership of entities. Further, students are asked to articulate the purpose and associated target audience that motivated their choices. In these ways, students are asked to consider how varied contexts or situations might suggest a different set of attributes for the same entity set. For the assignment, students produce a set of 10-15 attributes to define their entities in support of the purpose. They label and describe each attribute in sufficient detail such that others could assign values for entities of the type that they have described. For each attribute, they set parameters for acceptable values and provide guidelines that show how values should be expressed. A brief critical reflection includes their understandings of their design process and the resulting product. The primary strength of this assignment in the context of information pedagogy is that students are taught to think critically about designing an initial attribute set that contributes to a defined purpose for description, when and how it does and does not necessitate changes, and how to argue for how these changes reflect shifts in perspectives.

RELATED MATERIALS

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 Clement, Tanya. “An Information Science Question in DH Feminism.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 9.2 (2015): n. pag. Web. 25 Feb. 2016. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/9/2/000186/000186.html

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Feinberg, Melanie. “Two Kinds of Evidence: How Information Systems form Rhetorical Arguments.” Journal of Documentation 66.4 (2010): 491-512.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 Galloway, Alexander. “Are Some Things Unrepresentable?” Theory, Culture & Society 28.7-8 (2011): 85–102. Web.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 Ribes, David, and Steven J. Jackson. “Data Bite Man: The Work of Sustaining a Long-Term Study.” Raw Data Is an Oxymoron. Ed. Lisa Gitelman. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013. 147–166. Print.

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 Shaw, Ryan. “Big Data and Reality.” Big Data & Society 2.2 (2015): 2053951715608877. Web.

WORKS CITED

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 Buckland, Michael K. “Information as Thing.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 42.5 (1991): 351–360. Print.

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 Drucker, Johanna. “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 5.1 (2011): n. pag. Web. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/1/000091/000091.html

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 Edwards, Paul. “Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, Time, and Social Organization in the History of Sociotechnical Systems.” Modernity and Technology. Ed. Thomas J. Misa, Philip Brey, and Andrew Feenberg. MIT Press, 2004. 185–225. Print.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 Eliot, T. S. The Rock; a Pageant Play. London: Faber & Faber, 1934. Print.

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 Foucault, Michel. Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 Marche, S. (2012, October 28). “Literature is not Data: Against Digital Humanities.” The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://lareviewofbooks.org/essay/literature-is-not-data-against-digital-humanities/.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 Nunberg, G. “Farewell to the Information Age.” In Geoffrey Nunberg (Ed.), The Future of the Book Berkeley, CA. University of California, 1996: 103-133.

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 Pound, Scott. “Kenneth Goldsmith and the Poetics of Information.” PMLA 130.2 (2015): 315–330.

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 Sacasas, Michael. “Do Artifacts Have Ethics?” The Frailest Thing. 29 Nov. 2014. Retrieved from http://thefrailestthing.com/2014/11/29/do-artifacts-have-ethics/.

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 Sharma, N. (2004) http://www-personal.si.umich.edu/~nsharma/dikw_origin.htm accessed December 2004.

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 Stein, Gertrude. Reflection on the Atomic Bomb. Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1973. Print.

Comments

Comments are closed

0 Comments on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

0 Comments on paragraph 23

0 Comments on paragraph 24

0 Comments on paragraph 25

0 Comments on paragraph 26

0 Comments on paragraph 27

0 Comments on paragraph 28

0 Comments on paragraph 29

0 Comments on paragraph 30

0 Comments on paragraph 31

0 Comments on paragraph 32

0 Comments on paragraph 33

0 Comments on paragraph 34

0 Comments on paragraph 35

0 Comments on paragraph 36

0 Comments on paragraph 37

0 Comments on paragraph 38

0 Comments on paragraph 39

0 Comments on paragraph 40

0 Comments on paragraph 41

0 Comments on paragraph 42

0 Comments on paragraph 43

0 Comments on paragraph 44

0 Comments on paragraph 45

0 Comments on paragraph 46

0 Comments on paragraph 47

0 Comments on paragraph 48

0 Comments on paragraph 49

0 Comments on paragraph 50

0 Comments on paragraph 51

0 Comments on paragraph 52

0 Comments on paragraph 53